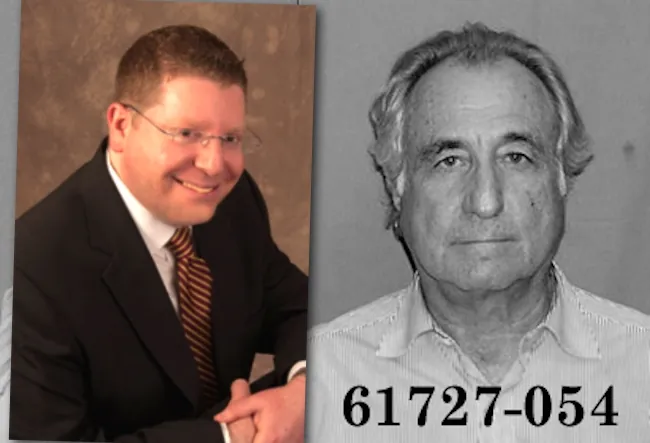

Maryland Professor David Weber (left) is using Bernie Madoff to teach students about fraud

David Weber has seen it all. The former chief investigator for the Securities and Exchange Commission, Weber has investigated misconduct ranging from cattle fraud to trade secret theft to Chinese military spying over a two decade career in public service. Over that time, he has learned one enduring truth.

“Fraud is only limited by the ingenuity of the perpetrator,” he tells Poets&Quants in an interview. “It is only limited by the capacity to engage in creative thinking.”

Perhaps the most imaginative hustler in recent memory is Bernie Madoff. During the 2008 financial meltdown, Madoff became the face of fraud, orchestrating a Ponzi scheme that bilked investors out of nearly $20 billion. Currently serving a 150-year prison sentence in North Carolina’s Butner Prison Camp, Madoff may seem more like a cautionary tale than a sage at this point. In Weber’s executive and online fraud detection classes, he brings a rogue’s voice to the table. In essence, he is a guide to what can go wrong, pointing out where individuals and organizations are vulnerable and what can be done to stop the perpetrators.

Sound like a replay of Catch Me If You Can, where Leonardo DiCaprio’s Frank Abagnale helps the FBI catch swindlers after paying his penance? Not exactly. Instead, Madoff operates in the shadows, reviewing course materials and answering student questions via email far away. One contribution: He evaluated Weber’s online course syllabus in advance, posting suggestions on what he felt was truly valuable to MBAs.

“He was very focused on the culture as a whole and the lack of understanding in both the accounting and legal professions in particular,” Weber shares.

FRAUD: THE TOPIC THAT DARE NOT SPEAK ITS NAME

Madoff may be the star attraction in Weber’s fraud courses. But once students roll in, it is Weber’s boundless enthusiasm and thought-provoking questions and experiences that leave a lasting impression. The University of Maryland’s Smith School of Business is known for embracing practitioners like Weber. In his courses, students apply real world tools, used by regulators and senior executives alike, to prevent Enron-like chicanery from engulfing their organizations.

A professional track faculty member, Weber considers his classes to be a labor of love. “I love fraud and ethics,” he proclaims “It’s my life. I live it and breathe it. If I was a private investigator in a noir movie, I would have a neon sign blinking in my office window saying, ‘Fraud! Fraud! Fraud!’”

His executive MBA course, “Fraud Detection and Deterrence in Operations,” is a one day seminar-style tour-de-force that the last Smith cohort voted to make required. Drawing 30 to 40 students, the class is more like a c-suite level briefing that’s supplemented by intensive pre-work. In contrast, the online version, “Fraud Examination Detection and Deterrence in the Business Environment,” includes a synchronous weekly lecture and delves into investigatory techniques. More intimate with 10-15 students, the online version will soon double from 5 to 12 weeks long due to rave reviews and its increasingly broad scope.

ONLINE STUDENTS GET ON THE STAND

Weber also customizes these courses to cater to his students’ unique needs. He estimates that three-quarters of his EMBA students are mid-to-senior level executives. While their focus is fixed on the big strategic picture, the diversity of industries represented means that they differ in what’s important to them. For instance, Weber cites that government contractors fretted over the risk of information theft, while pharmaceutical execs centered on their exposure to False Claim Act allegations. The online class, which is populated by the likes of military officers and comptrollers, were more dialed into the nuts-and-bolts processes related to identifying and dealing with fraud.

A case in point is the online course’s deep dive into giving testimony. For Weber, fraud is an inevitable part of business — as is being sued. As a result, he believes MBAs should be prepared to someday bear witness. Normally, this is a reactive process, where a big law firm coaches executives for deposition. In Weber’s class, online MBAs get a head start, learning both the legal process and communication fundamentals.

“We’re not teaching people how to lie,” Weber emphasizes. “We’re teaching them how the system works and how important it is for you to be able to explain complicated business concepts in way that a lay person would understand. The decision-maker is ultimately going to be a judge or jury who don’t have an MBA from a top school. So how would you go about explaining what the situation is in a way that an ordinary person at a cocktail hour or a county fair might understand?”

TO CATCH A THIEF, YOU NEED TO THINK LIKE ONE

The executive course, in turn, relies more heavily on case studies developed by the Center for Audit Quality. These studies focus on teaching executives about their corporate governance roles in what Weber calls the “reporting ecosystem” (i.e. a board of directors, audit committee, board subcommittee, divisional controller, etc.).

While Weber notes that business schools often highlight how to boost revenue and productivity, he argues that intricacies like reporting structures and internal controls are also key parts of MBA education. “Before they get out of the program, students need to understand their personal role in the corporate governance ecosystem,” he notes. This is particularly true for executive MBAs, who may already be part of the chain of governance. “By having a course focused on understanding the roles and responsibilities of each member of the chain,” Weber points out, “MBAs get to pause and think about how each might be designed to perform better when they return to their employers, as well as where problems might occur in their real world jobs.”

Both courses, however, begin with students engaging in what seems a heretical exercise: They are asked to think like criminals. “We close our eyes and we think, ‘OK, each of you in this program is an executive or an up-and-coming person within the organization. Ask yourself: How could you do it if you wanted to? How could we circumvent internal controls and what is the worst thing that you could do in your organization?’ Then, ask yourself, ‘what do we need to do to fix it to prevent this from happening?’”

According to Weber, the exercise stems from Section 404 of the Sarbanes Oxley Act, affectionately known as SOX. This act enforces executive accountability by requiring them to maintain internal controls over financial reporting. It also calls for public auditors to do more than take numbers at face value and imagine doomsday scenarios. The exercise itself introduces MBAs to how regulators approach fraud during an investigation. “We would get cases and a lot of times it was like a car crash,” Weber explains. “It is very hard to understand how this became a sausage from when it started out as a cow. The answer is, we would have to brainstorm and work backwards to figure out how was crime was committed.”

NEXT PAGE: How Bernie Madoff chose Weber’s fraud prevention textbook.

Questions about this article? Email us or leave a comment below.