A photo of a the Wharton Wives Club MBA Coffee Hour from the 1960s. Photo courtesy of the Wharton archives via Allison Elias.

The first woman MBA candidate graduated from The Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania in 1931 — but it didn’t open the floodgates. Twenty years later, in 1951, only six women were enrolled in Wharton’s MBA.

One of Wharton’s Ivy and M7 rivals was even slower in accepting women into its student ranks. The first eight female students didn’t enroll in Harvard Business School’s two-year MBA program until 1963. They did so alongside 676 men.

Despite more recent and often heralded gains for women in business education, men have long dominated both graduate business programs and corporate leadership. But that doesn’t mean women weren’t also at business schools during the early decades of graduate business education, at the start of the still-unfinished march toward parity. It’s just that they were often invited to be there as support for their executive husbands.

“There’s two sides to the story,” says Allison Elias, an assistant professor of business administration in UVA Darden’s MBA and EMBA programs. “In one way, we think this increases the agency of looking at women in the past because maybe they weren’t part of degree programs, but they certainly were part of their husband’s career success and his professional growth.”

ROLE OF WIVES IN EXECUTIVE EDUCATION OF THE ’40s and ’50s

Allison Elias

“On the other hand, it does help us understand that women for so long had been excluded from the higher status classes and degrees that men had access to,” Elias continues. “For example, at Harvard, they used to shuffle women to a one-year business administration program at Radcliffe that was more of a personnel training.

“The story there is just that women had separate schooling, separate training, and now here we are trying to integrate everybody.”

Elias and her research partner, Rolv Petter Amdam of BI Norwegian Business School, recently published a paper examining the role of such programs, “Business Schools and the Role of the Executives’ Wives.” It was published in a special issue of the Academy of Management Learning & Education.

THE MAKING OF A MANAGER WAS A FAMILY AFFAIR

The paper examines B-school programs of the 1940s and ‘50s for the wives of their enrolled executives — which were almost all white men. In the short programs, typically about a week, women took courses on current events, domestic upkeep, and how to support their husbands’ careers. They learned about executive socialization, formed tea clubs, and took classes with titles like, “The Care and Feeding of Your Executive Husband.” For the historical perspective, the authors searched through the historical archives of several top business schools and studied contemporary media reports, articles and literature. They found that at the time, the making of a manager was considered a family affair.

In a presentation for the Wharton School, Elias noted that nearly half of corporate leadership roles had “wife screening,” to ensure that the executive’s wife was “suitable” for the corporate culture. In one company, up to 20% of corporate hires were rejected because of their wives. At Wharton during this time, the MBA Wives’ Club hosted tea parties and other social events while helping furnish dorm rooms. At Harvard, women attended dancing classes, learning the latest steps in the “Cha Cha Cha, Calypso, Boogie Woogie, Tango, and the Waltz.”

P&Q talked with Elias about her recent paper, the concept of the corporate “ideal worker,” and how the past experience of women in business education informs efforts to increase accessibility today.

Q&A WITH DARDEN’S ALLISON ELIAS

P&Q: What made you start researching the education programs for executive wives?

Allison Elias: I’m a historian by training, and I got into this research about women in business schools through women in the workforce more generally. I was thinking about the tension between to what extent women choose a career versus to the extent they’re sort of shuffled or pushed by norms towards certain things. I wrote the paper with a scholar, Rolv Amdam, who’s a specialist in the history of executive education, and he actually found some things in the Harvard archives about these sorts of training classes for the wives, and he approached me as a gender historian. That is the background to the article.

What interested you about these classes for executive wives?

What was really interesting to me was we have this idea in the way we sort of tell the narrative of women in business schools that they had never been there until now that they are 40 or 50% (of the cohorts). You know, we talk about the demographics as if they weren’t part of the whole enterprise before. What we found fascinating was the fact that, actually, the older idea of a corporate man or a corporate leader really was almost a pair. The assessment of the wives was incredibly important. We found material that a lot of times interviews would take place with the wives and people would be turned down because their wife maybe wasn’t appropriate or didn’t have the right network or didn’t engage in the right activities.

What kinds of things would be happening in these executive classes?

It was really about becoming a, you could say, a person of high culture and learning manners. They really varied from school to school. At some schools, it would be more about the women educating themselves on current events, but it could be more domestic pursuits such as flower arranging or square dancing. There is sort of a big range. In particular, we found some programs about women learning more about what their husbands careers would be like. So, how to support their husband, how demanding it would be to be married to an executive, what was expected as far as providing social outlets for the company, and being present to support his leadership role or his presence in front of the company.

We have evidence that these wives programs in executive education offered some activities for wives only such as concerts, cocktail parties, educational lectures, off-site company visits, case studies, and bridge. But also the wives also participated in husband-wife social events and even in their husband’s final presentations to the class. In this way, the wives learned more about their husbands’ careers but also participated in the socialization process of a new business elite.

What resources did you mine to find this information?

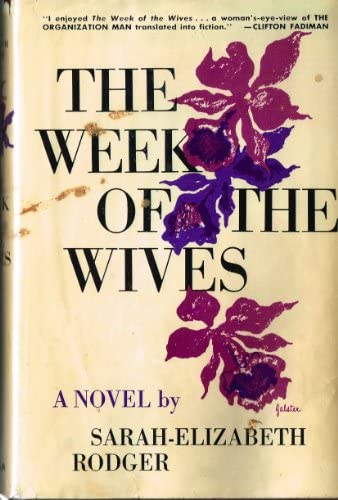

We looked at the historical archives of Harvard Business School, MIT, Wharton, and Stanford as well as academic literature, popular business articles, media reports, and the literary novel, “The Week of the Wives.” A topic like “socializing wives” is less visible in the historical record, so we combine different types of sources, both published and unpublished.

We looked at the historical archives of Harvard Business School, MIT, Wharton, and Stanford as well as academic literature, popular business articles, media reports, and the literary novel, “The Week of the Wives.” A topic like “socializing wives” is less visible in the historical record, so we combine different types of sources, both published and unpublished.

Everyone knows the book by sociologist William Whyte, the organization man. He actually had a series of articles in Fortune Magazine about the role of corporate wives in the ’50s. “The Week of the Wives” is a novel about a woman going to Harvard for the week after an executive education seminar. They would bring the wives for separate training, but also just to kind of go to dinners with the group and meet other professional couples.

So the purpose of going to dinners and those kinds of things was to make sure a husband would be able to take his wife to meet his boss, that sort of thing?

Yes, exactly.

Interesting. What were some of the most striking or significant findings you found in the research?

I guess one thing that I found striking is the idea that the wives were so pivotal to their husband’s career success. They were so important, in fact, that the business schools, I would say, followed the corporate norms and values of the time. Corporations were engaging and kind of fact finding on the wives, bringing them into interviews or having them be part of interviews with their wives. I think business schools saw that there was a need to, you know, “train” the wives.

I find it interesting that there was, I mean obviously, this was a body of white men and women. So there was this normative idea of what a corporate wife does, what she looks like, and how she’s supposed to behave. That obviously is limiting as we tried to move forward at business schools and in corporate America.

Yes. Your paper, in fact, talks about the concept of the “Ideal Worker” in corporate culture. Can you explain that a little bit more?

So, a lot current literature on the limitations women face at work is about this “ideal worker,” which just means the idea that a person (or basically a man) would be able to devote his full attention and energy to the corporation and to his career because there was someone at home taking care of domestic issues as well as raising children. We talked about how some careers are just really demanding and demand all of your attention, and the idea is that these are harder for women to enter and harder for women to be successful in because of the “ideal worker” norm. We were basically saying that our historical research helps to inform the way that gender has been imprinted both on corporations, but especially on business schools, and there is a longer history of training men for one sphere of activity and training women for a separate sphere of activity. And it wasn’t that the women’s sphere didn’t actually bolster men and their activities, but just that there were separate spheres that men and women were expected to inhabit.

How do you think the concept of the “ideal worker” has changed in business education?

I think the rise of part-time programs and MBA education having more flexibility helps to mitigate this “ideal worker” image. The idea is that maybe you can’t fully devote yourself to an MBA, but you can put parts of your energy and life towards it.

I would say that we still do in some ways expect employees to devote themselves to business school. For example, even just forced grading curves, I think, fosters this type of competition among students that rewards the person who is able to work the longest hours and be best prepared for class. All the networking that MBA students have to do to get jobs is another example. When I hear about all these sessions that are held from, like, 5 to 7 p.m., it’s a lot of work to land that internship. Obviously, people who have to be caretakers to others are more limited in their availability. I know that there’s a few women at Darden who are mothers, and I’ve talked to them about just the recruiting expectations being hard to meet because they are a lot of time outside of traditional working hours.

What do you think can be done to make business education more accessible to women now?

Besides offering more flexibility in the format of the MBA, which I think schools are starting to adopt, I think that the full-time residential programs could look into trying to offer ways to be more supportive to families, and maybe even–I know this is gonna sound kind of radical–but offering childcare or helping to facilitate childcare for men and women who have small children but need to spend long hours doing recruiting, networking, things like that.

Tell us about where we can find the paper.

It was published in a special issue of the Academy of Management, Learning and Education Journal, and the issue is all about new ways to think about the history of business schools.

What is the value in looking into programs that are, you know, 70 to 80 years old? How does it inform what’s happening now or what can be done differently?

I think it can inform the way we recognize that the whole structure of MBA programs and a lot of corporate jobs have been around the idea of this “ideal worker” norm, and not around, you know, a dual career couple or some who doesn’t have somebody else to take care of personal domestic child care matters.

Women@Darden Initiative works to develop leaders and support women MBA candidates. Here, women business students gather as part of the Graduate Women in Business Leadership Conference in November. (Photo courtesy UVA.)

I would like to say it also elevates the idea of the role of those who are supporting a corporate professional and sort of thinking about the ways that that has been really pivotal. You know, the person sort of behind the man or behind the executive. Actually, these support roles have been in the past really pivotal to careers. What we did with all of the EEO (Equal Employment Opportunity) laws is we basically said you’re not allowed to ask about people’s families anymore. You’re not allowed to ask about kids, and I think that tried to create a gender neutral way to get around the unfairness to women, but in the past women did contribute in a lot of ways to their husband’s career and to business school life.

What else should readers know about?

I should mention that at Darden, we have a Women at Darden initiative to provide resources and channels to increase representation of women.

I guess when I think about the way the Forte Foundation, as well as schools, talk about women in business schools, it’s all about just the composition of the class. It’s like, “Okay, we have 50% now. Yes, we’re there!” This, to me, is the whole diversity versus inclusion thing: You can bring in women, they can sit in the room, but do they feel included? Are their values and experiences part of the culture, the fabric of the institution? I guess my sort of critical view when I read about women in business schools is that while it is important to focus on the actual quantity and presence of women, but in what ways does that help to change the business school or inform the future of where business school is going? What Darden is doing is trying to not only increase the number of women, but also to help make sure women have more opportunities for non-traditional careers.

Questions about this article? Email us or leave a comment below.