Maddox had not been trained to inflict pain in an attempt to gather information, and hadn’t even known it was an option, he says. “I didn’t know how to torture. It’s not my nature. I don’t spank my kids.”

LIARS, LIARS, EVERYWHERE

It took him about 50 interrogations to figure out how to “get in prisoners’ heads,” he says. The techniques he developed, he would later discover, applied to ordinary citizens as well as to murderous gunmen: as a militant will lie about the location of a weapons cache, and a job applicant will lie about the real reasons for leaving a previous position, a borrower will lie about income or concealed debt.

“If you’re a banker and somebody’s trying to get a loan, are they really going to be transparent about their financial situation? No. They’re gone to take advantage of deception either to get the money or to get a lower interest rate,” Maddox says.

And will a college basketball star being scouted for the NBA draft speak forthrightly about his lifestyle, so teams will know whether he’s a high risk for problematic behavior? Not likely.

“He’s not going to come out and say, ‘I can’t stop smoking dope,’” Maddox says.

So, when a prisoner refuses to name a location, or a job seeker nudges an interview away from her employment history, or a would-be homebuyer pulls numbers out of thin air, or a seven-foot-tall 22-year-old declares that he spends weekend nights crocheting with his grandma, how do you find the truth?

EMPATHY AS A STARTING POINT

“Initially, what you want to do, you’re gonna convince the person that being transparent does benefit them,” he says. “You start by covering your questions under the umbrella of empathy towards them, caring, kindness, to sort of build that atmosphere, and then what I would do is sort of probe questions from different angles, not necessarily to gather the truth at least at first, but to probe an issue from different angles to kind of see why they’re lying about it.”

However, confronting someone with a lie they’ve told is often counterproductive, he says. “When I catch them in lies, I have to set up for them a nice easy out to justify their accidental unintended lie to me before we can get beyond that. You give them an out on the lie . . . you give them an out on being the bad guy. Many times the prisoner will talk if they can save face.”

In many business contexts, the truth may be seen as an asset by one side in a deal and a liability by another, Maddox points out. The builder in a construction project may know it will take nine months to complete, but say it can be done in five. A skilled interviewer would give the builder what amounts to ready-to-use excuses for low-balling time-to-completion: “the weather has been so detrimental” or “the new laws slow the process.”

“You set out a path for them to reveal the honesty,” he says. “Otherwise you’re humiliating the person by catching them in the lie.”

GET OUT OF JAIL, BUT NOT FOR FREE

With Iraqi captives, Maddox would make promises, he says. “I’ve got to get them to understand that by talking to me their situation’s not going to get worse, it’s going to get better. I have to give them massive amounts of hope. I have to build them a pathway to achieve their goals, which for most prisoners is to be free.”

Sometimes he would promise that if the captive provided information, Maddox would make sure the man’s fellows wouldn’t know who was responsible for the leak. Sometimes he would guarantee the prisoner’s freedom in exchange for information, he says.

“You get them to understand that you’re really going to come through on those promises, the prisoners are going to talk really quick, they’re going to break,” he says.

In Tikrit, Maddox’s interrogation results earned him the trust of his commander and the Delta Force soldiers, he says, and the soldiers would back up his promises, freeing captives Maddox had enticed into truth-telling through pledges of liberty. As his interrogation methods improved, he was getting cooperation from prisoners 65% of the time, compared to the 4% typical in the U.S. military after 9/11, Maddox says. But he could get little traction up the chain of command for his belief that Saddam was in Tikrit. “Their logic was, ‘Hey, we dropped 15,000 soldiers into this town of Tikrit that has 20,000 citizens, we’ve been to every house, why should be believe that Saddam is here?’”

BIGGEST BREAK IN THE FINAL HOURS

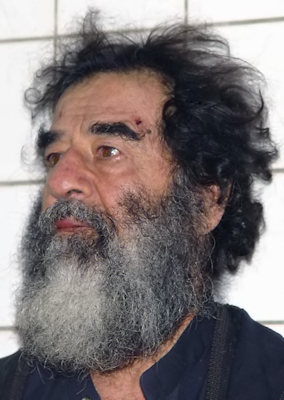

In mid-December of 2003, Maddox’s deployment was wrapping up. The whereabouts of al-Musslit, and Saddam, remained unknown to the U.S. military. About to fly home, Maddox brought a group of prisoners from Tikrit to Baghdad. And then one of them broke, and revealed not only that al-Musslit was in Baghdad, but was staying in a particular house. Delta Force hit the house. Maddox came to see the prisoners, and when he pulled the hood off one, he recognized the elusive bodyguard by his chin.

Maddox had leverage: al-Musslit had involved his male family members and friends in his work for Saddam, and during the hunt for al-Musslit, many of them had been picked up and imprisoned. Maddox promised him that if he revealed Saddam’s location, the family members and friends would go free. The interrogation had started at 4 a.m. on Dec. 13. Maddox’s flight out of Iraq was to leave at 8 a.m. At 7:45 a.m., al-Musslit broke.

“He said, ‘I’ll go, I’ll take you right now,’” Maddox says. Delta Force took al-Musslit to Tikrit, and The Fat Man led the commandos to Saddam’s spider hole.

Questions about this article? Email us or leave a comment below.